Travel Notes from Summer

From the pavement that twists around Seneca Village in Central Park, to the shoreline of Martha’s Vineyard, to the memories of Highland Beach in my father’s drawings, and more — I’ve spent the summer in deep exploration with how nature has served as a refuge and a catalyst for Black legacies.

Most recently, I took a few team members on a walk through Seneca Village, the Ramble, and North Woods, asking them to take note of what nature teaches us about nourishing Black brilliance and imagination. What unfolded were divine truths — or revelations — about the role of the natural world to generations of Black legacy architects.

Sites of Resistance

There is trauma that exists and continues to exist for Black communities in so many elements of the natural world — and, yet, there are also very real and lived experiences in the feelings of being held by the natural world. In the feeling of being protected and sheltered from the duality of life as Black humans in America when immersed in the natural world.

In her book Rest is Resistance, Tricia Hersey documents the history of the American maroons — Black legacy architects who resisted the dominant narrative of enslavement by organizing “themselves to survive and thrive” by creating “a whole world within an oppressive one to test out their freedom and regain autonomy.” Often, this was done through retreating into the natural world — into the woods, caves, and seemingly small bushes in gardens — to create spaces and places where they could disconnect from the violence of slavery, where they could just rest, where they could just be.

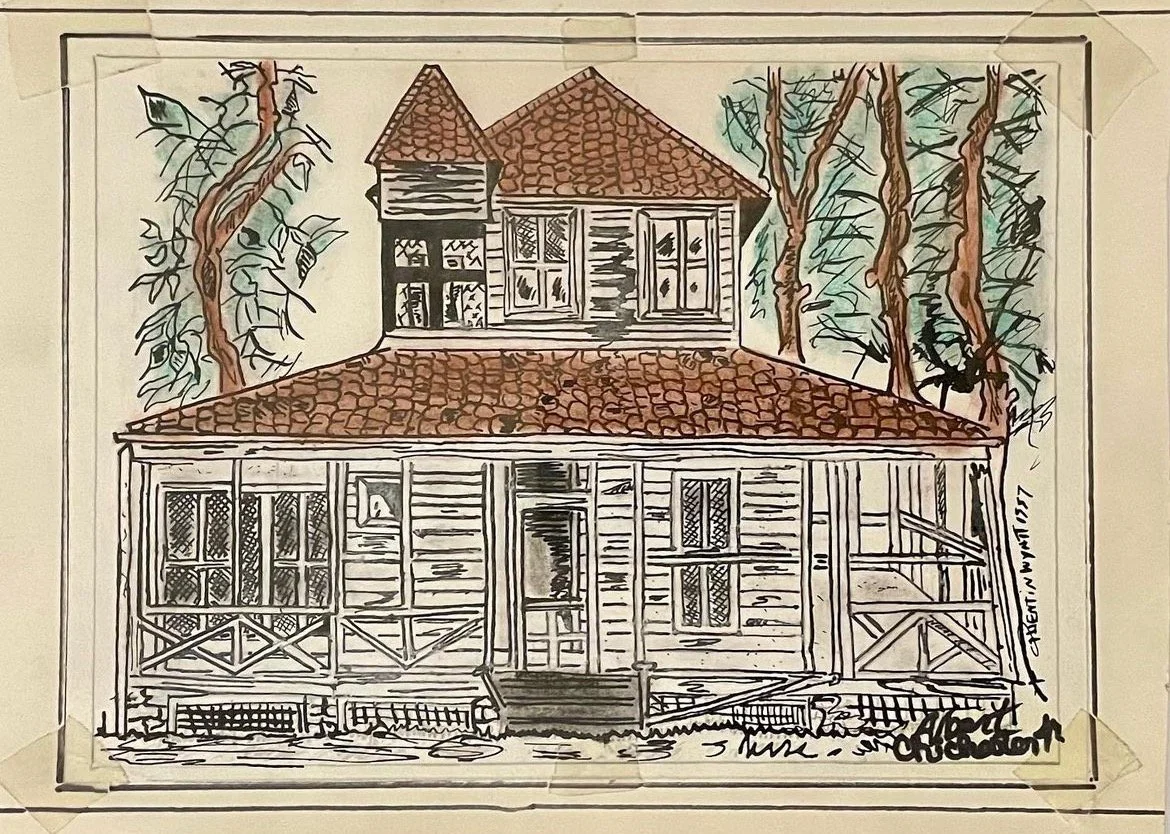

Twin Oaks, Highland Beach | As depicted by my father, Quentin Wyatt

As I think about the history my father passed onto me about Highland Beach, I see the same lessons in resistance. The legacy architects Highland Beach reimagined the discriminatory capitalist system that was the backdrop of Black American life. A system that would evolve slavery into Jim Crow into redlining and more. And yet, Highland Beach would become a refuge for Black legacy architects like Frederick and Charles Douglass. Its beaches and tall oak trees would become a tucked away place to build multigenerational wealth anchored in collective healing and care.

When I walked Central Park with my team last month learning how nature has nourished Black imagination, I thought about the maroons and the original families of Highland Beach with nearly each step. I daydreamed about how they might have felt the pull of the natural world — from the meditative sounds of waves against the shoreline to the calming bird song. I daydreamed how they felt protection — from the sturdiness of the land holding up their bodies as they laid down to rest in the grass to the shade of the tree canopy.

And as I walked, I wondered: how is my generation continuing to build on this blueprint of finding refuge and safety in the natural world? Of finding these spaces of resistance? How are we passing down this blueprint to future generations?

Legacy Vision Boards

I’ve come to believe after countless walks through Seneca Village, the first section of Central Park I walk at least once a day, that the village is a passed down legacy vision board for me on the redefinition of wealth and relationship to land.

For those of you who do not know Central Park well, Seneca Village is located on the west side of the park and can be found at the 86th street entrance to the Great Lawn. In 2011, the City of New York began to uncover the legacy of Seneca Village and soon and signs documenting the limited history that was found began to pop up on my walks. Despite the limited codified history, what has unfolded for me is a legacy vision rooted in a holistic definition of wealth.

The pioneers of Seneca Village sought to find refuge in the park at a time where the majority of the island’s residents — particularly if they were Black — lived in deteriorated and crowded housing at the bottom of Manhattan. The pioneers found refuge in the stretch of lush green canopies and fields from the unhealthy conditions and racial discrimination they faced downtown. For me, they built on the legacy of the maroons: they found refuge in nature… and then they found their vision.

They laid a vision of generational wealth deeply rooted in faith, community, ownership, autonomy, lifelong learning, and wellness. The community of Seneca Village chose what they ate, caring for livestock and planting multiple gardens. Lifelong learning was prioritized; they laid the bricks and mortar of multiple schools. Spirituality guided them, and their churches would eventually expand beyond the island.

As I think about the legacy vision board the pioneers of Seneca Village left us behind, what stands out the most as their modeling of a partnership with the natural world. It was not the dominant narrative of an extractive relationship. They partnered with the land to create shelter and food sources. And they also honored the boundaries of the natural world. The heart of the village was Summit Rock — a place of immovable rock that was never tinkered with or built upon. But rather, honored and maintained in its natural state.

Today, Summit Rock remains untouched.

The Space to Rest and Reimagine

As I was preparing for my first trip to Martha’s Vineyard, I found myself lost in the pages and history of the island in Jill Nelson’s Finding Martha’s Vineyard: African Americans at Home on an Island. In it she chronicles the stories of mostly Black women and their legacies of finding refuge and creating legacy in partnership with the natural world. What struck me about the stories she weaves together is the consistent presence of spaces to rest and reimagine in their legacies against the backdrop of nature.

We’ve all likely been on the full itinerary vacations (the kind where you need a vacation from your vacation!), but Nelson describes a space that’s easeful and emergent on the Vineyard. She describes the flow of days for many anchored in time in the water, movement, and community. They are never seemingly rigid, rushed, or over-stacked schedules, but rather they are malleable schedules. Nourishing schedules. Flexible schedules. Restful schedules. The schedule of the Vineyard almost seems ritualized: arrive, go to your favorite place on the island as a changed human from the summer that came before, unpack, swim, write or draw, nap, take in the sun, read, laugh with friends and family, sleep. Repeat.

As the rituals of rest sink in, so too does space to reimagine. Nelson writes about how the Vineyard was a place of reinvention and expansion for her mother and friends in the summers — a place where they were “freed from the constraints of identity, habits, and expectations, the parameters of who they were nine months of the year, if not fully erased, then definitely blurred, and they could reinvest themselves. [They could] pursue dreams and interests that there was little or no time for the rest of the year.”

“Lost souls have long retreated to to the seaside to take in the air. But only here, where concrete ears manifest the invisible, does the purpose become clear…the air is a place of letting go. Its business is dispersal, the dissipation of fog. The scattering of seeds. Subtly, imperceptibly, air brings in the new.” - Katherine May, Enchantment

As I walked the shoreline and weaved in and out of the brick-lined streets, I couldn’t help but to think about Katherine May’s description of the feeling of sea-salted air. Of the alchemy of nature, rest, letting go, and beginning again. I felt rooted in this alchemy that, perhaps, was the ethos of the Vineyard’s legacy of nourishing Black brilliance and imagination. An ethos of rest, an ethos of creativity, an ethos of centering the natural world in imagination, an ethos of shedding our skins from the winter and spring in order to make space for the new.

The Dream Keeper

Bring me all of your dreams,

You dreamers,

Bring me all of your

Heart melodies

That I may wrap them

In a blue cloud-cloth

Away from the too-rough fingers

Of the world.

“The Dream Keeper” by Langston Hughes

My summer travels through nature have nearly come to a close — but the their revelations continue to unfold. As the season begins to shift, I’m sitting with the truth that emerged consistently on my walks this summer, about how Black brilliance and legacies have been nourished, held, and sustained over generations: the natural world has been our Dream Keeper.

It has been the blue cloud-cloth that provides refuge.

It has been the heart melodies of bird song that have eased us into nourishing naps.

It has been the strength of the Earth holding us up, even on our weariest of days.

And yet, as our summer’s heat marked one for the history books, I wonder and worry about how we protect the natural world’s invaluable role in our legacy-making. I wonder: how are we partnering with the natural world as we resist, rest, and imagine? What can we learn from Black legacy architects and how they honored lands like Seneca Village, Highland Beach, and so many more? How are we caring for Mother Earth, creating spaces for her own refuge and rest?

The natural world has been the Dream Keeper to Black legacy architect for generations. Now it is up to us to be a Dream Keeper back to Mother Earth.

In still of revelations,

Gabrielle